Ben Shahn

Ben with mother; Gittel nee Lieberman

and younger siblings; Philip, born in 1900, sister Hattie in 1902

Ben with mother; Gittel nee Lieberman

and younger siblings; Philip, born in 1900, sister Hattie in 1902

Ben

Shahn American

artist,

muralist, social activist, photographer and teacher. He is

best known for his works of Social

realism, his leftist political views, and his series of lectures published

as The Shape of Content.

He was

born in Kovno on September 12th, 1898 , to Joshua Hessel and Gittel (Lieberman) Shahn.

His father was exiled to Siberia for alleged revolutionary activities in 1902, at which point

Shahn, his mother, and his three younger siblings moved to Vilkomir (Ukmergė).

In 1906, the family

emigrated to America where they rejoined Hessel, who had fled Siberia. They

settled in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn, New York. Shahn began his path to

becoming an artist in New York, where he was first trained as a typographer.

Shahn's early experiences with typography and graphic

design is apparent in his later prints and paintings which often include

the combination of text and image. Shahn's primary medium was egg tempera,

popular among Social Realists. On August 8th, 1922 Ben married

Tillie Goldstein

He was

recommended by Walker Evans, a friend and former roommate, to Roy

Stryker to join the photographic group at the Farm Security Administration (FSA),

traveling and documenting the American south alongside Walker

Evans, Dorothea Lange and other photographers. In May and

June 1933 he served

as an assistant to Diego Rivera while Rivera executed the infamous Rockefeller Center mural, and by circulating a

petition among the workers, Shahn had a role in fanning the controversy. Shahn

left the FSA in 1938,

and that same year he and his wife Bernarda moved to the new town of Jersey

Homesteads (now Roosevelt, New Jersey).

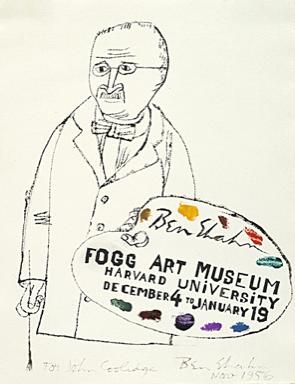

In 1975, the Harvard University Press published The

Photographic Eye of Ben Shahn, which has a collection of his works.

1910 United

States Federal Census

about Henry Shahn

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

![]()

Save This Record

|

In 1906, shortly after Ben Shahn arrived in the United States, he became aware of what he later called "the whole business of the Mayflower and ancestry." He was eight years old and had been taught that Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, the great biblical figures, were his ancestors, and they seemed unquestionably more directly related to him than did Columbus and the Pilgrims. It was puzzling. He recognized that he had parents and two sets of grandparents and many aunts and uncles, but he knew nothing of the kind of ancestry that appeared valued in his new country. In an attempt to establish this lineage, he nagged his father incessantly. He knew that his father was a woodcarver, as were his father's father and his father's grandfather, but he wanted to know more. Finally, exasperated, the young boy's father answered by drawing a picture of a man on a gibbet. When Ben wanted to know who that was, his father angrily answered that the man was an ancestor, a horse thief, adding, "If I ever catch you asking about ancestors...! Only what you do counts, not what your ancestors did."

In spite of these words, there is no doubt that many of Ben's characteristics can be traced to his ancestors. His father, Hessel, born in 1871, was a skilled craftsman who loved to work with his hands, as would his son. He taught himself to draw at an early age, as would Ben, and he was a born storyteller, just as his son would become, in his art as well as in his conversation. Finally, Hessel was an idealist, whose liberal political convictions must surely have influenced Ben.

Ben's mother, Gittel Lieberman, born in 1872, was descended from a family of peasants, but her father educated himself and became an innkeeper, and later even worked as a schoolteacher. She, too, was a natural storyteller, whose fanciful tales delighted her son. One of many children, she was apprenticed as a kind of indentured servant to a wealthy family of wholesale grocers. Because she was a girl, she wasn't taught to read or write --she was taught these skills by her husband, after their marriage--though she learned to work as a bookkeeper, making out invoices in a language she couldn't understand. Gittel was strong-willed and keenly intelligent, as was her son. She was often described as quarrelsome and angry, as Ben would become.

"Most facts are lies; all stories are true," Ben told his friend Edwin Rosskam. And Ben told many stories. If a large number of these were invented, they are still worth recounting; they reveal as much about the artist as would the truth. He was the sum of his stories.

Certainly his memories of his earliest years in Kovno, where he was born on September 12, 1898, were, inevitably, confused--and, as he admitted, most likely inaccurate, since he spent only four years of his life there. These early memories include brutal incidents of religious discrimination and political terror. At the time of Ben's birth, Kovno, where more than 25,000 Jews lived (they made up approximately 30 percent of the town's population) was a center of Jewish cultural activity. These Jews lived in their own section, separated from the Gentiles. Crossing the non-Jewish sector was so dangerous that they walked through it hurriedly, never strolling in a leisurely fashion. They were even harassed at home and at work. Many Russian soldiers were stationed in Kovno, and when these recruits, most of them far from home, drank too much, they would smash the windows of the Jewish-owned homes and shops. Ben remembered a rock coming through the window of the Shahn home at least once. His family knew, however, that it would be futile to protest since any complaint to the authorities would be considered anti-czarist and result in harsh punishment.

Not all of Ben's memories were unhappy ones, however. On occasion he enjoyed playing with friendly soldiers on the parade ground where military drills and maneuvers were held. In Kovno, he ate ice cream for the first and only time before moving to America. An Armenian or a Turk carried on his head a huge wooden bucket filled with a container of the sweet frozen dessert, packed in ice. There was an uncle who played him to sleep with his trumpet each night when he stayed with Ben's family while on furlough from the army. And Ben remembered with great affection his father, whose stories entertained him, and who carried him on his shoulders to large gatherings, most likely socialist meetings.

Ben was too young to remember the birth of his brother Philip in 1900, but he did recall the birth of his sister Hattie in June 1902, when he was not yet four years old. She was born in a small room, separated from a larger one by a curtain with a peacock design; an old man--a cousin or a neighbor--sat on a nearby stool, cutting his toenails so close to the flesh that each toe bled.

That year of 1902 was a traumatic one for the young child. Not long after the birth of his sister, his father, politically active as an enemy of the czarist government, was arrested by the authorities. According to Gittel, her husband had been framed--revolutionary leaflets, she maintained, had been planted on him. However, in spite of her pleas, Hessel was exiled to Siberia, leaving his wife alone to bring up their three small children, and his eldest son heartbroken at the loss of a father.

Shortly after Hessel's departure, Gittel decided to move back to Vilkomir, forty miles away, where she and her husband had been born. A river divided the town, and the two parts were connected by a bridge. Most of Vilkomir's more than 7,000 Jews (half the population of the town) lived "across the river." Gittel's friends, as well as her parents and Hessel's, still lived in Vilkomir, and she felt certain that life would be far easier for a single mother there than in Kovno.

In Vilkomir, Ben formed one of the deepest attachments of his life, with his paternal grandfather. He also first learned to express himself through drawing, and began to question the fundamental doctrines of his religion.

Ben's paternal grandfather, Wolf-Leyb ("Wolf-Lion"), was a huge man, known throughout the village for his enormous strength and for his kindness and warmth. He became, for his young grandson, not only a surrogate father but also a genuine hero. He was so successful as a carpenter, making baroque furniture for a pope of the Orthodox church, that he eventually had half a dozen men working for him and therefore could spend all the time he wanted entertaining Ben. He did this with great love and enthusiasm. He constantly made things for the boy, carving out a little cart with a goat and any number of other toys, as well as teaching Ben how to carve objects himself--most memorably, a multiple-link chain, out of a single piece of wood. Wolf-Lion was always kind to Ben, even while disciplining him, which he did with tenderness.

Ben's maternal grandmother, a tiny woman, was also unfailingly sweet to him. Her husband, however, Ben's first teacher, was a redheaded tyrant, who was luckily soon replaced by a somewhat more understanding instructor. And despite the tyrant's brief reign, for the most part Ben, the oldest grandchild, was spoiled, so much so that his mother summoned help from her own brother, a rigid disciplinarian. According to Ben, he resembled a bearded Protestant minister with his black coat and white collar, and he had no influence on him whatsoever.

One of Ben's childhood memories was of a powerful fire that destroyed most of Vilkomir in 1902. Terrified, he walked through the charred town with his grandfather, whose five or six houses, since they were on the outskirts, were among the few not damaged. It was frightening: the fire bursting out everywhere, hundreds of people standing in the shallow river, carrying chests of drawers and bedding, in an effort to save themselves and their belongings. Lines of men formed a bucket brigade from the river, and in the background the blinding light of flames illuminated the burning town. This devastating fire left an indelible impression on him. Raging flames became a symbol of destructive power in many of his paintings and drawings.

Most important, in Vilkomir Ben learned to draw. Drawing came naturally to him; and he was always encouraged to draw whatever he could not explain in words. Because very little paper was available, he made most of these drawings on the flyleaves and inside covers of books. In Love and Joy About Letters, published in 1963, Ben described his first drawing, a portrait of his uncle Lieber, a member of the Russian cavalry, who, Ben was told, rode a horse and was very far away. Though he had never seen or met him, the boy was certain that his uncle was famous, because his family spoke of him so often and with so much respect. He wrote of this portrait:

"Since the only military installation that I had ever known was the striped sentinel box at the caserne at the end of our street, I drew my uncle sitting on his horse in front of that. The stripes were nice, but the horse troubled me because it looked like a cow--at least it looked more like a cow than a horse." To make sure that no one mistook the horse for a cow, he placed a caption, "Uncle Lieber Sitting on His Horse," beneath the drawing.

Ben's early formal education consisted almost exclusively of Bible and Talmudic studies. A precocious child, he was placed in a class with older students. They worked diligently for nine hours a day, studying the Bible, putting letters together to make its words, and studying its prayers and psalms. Discipline was severe; students who arrived late were whipped. Ben learned one important lesson at school: to despise injustice and fight it vigorously whenever and wherever he found it. He was enraged, for instance, by his teacher's practice of punishing the entire class for something that only one student had done. He hadn't done it, he would insist, and he wouldn't tell who had (if he knew). He categorically refused to pay for something for which he was not responsible. "I hate injustice," he told an interviewer in 1944. "I guess that's about the only thing that I really do hate. I've hated injustice ever since I read a story in school."

He repeated that story throughout his lifetime. It was a part of his Bible studies, and it concerned the building of Solomon's temple and the carrying of the Ark of the Covenant into that temple. According to the story, the Ark was to be brought in by two oxen; it rested precariously on a pole laced between them. The Lord warned that the pole would inevitably totter, but demanded that no one touch it since it was God's Ark, and He would take care of it. This was a test of faith. Of course, the Ark did totter, and one man did touch it, instinctively, in order to stop it from falling. Immediately, as he had been warned, the well-intentioned man was struck dead.

Young Ben, enraged, began to argue with his teacher. God was unjust, he insisted, and he refused to return to school until this injustice was officially admitted. After a week or ten days, and endless discussions between his teacher and his grandfather, Ben returned to school. "I must have compromised," he told an interviewer many years later, "probably my first compromise."

At this early age, Ben began to challenge the fundamental beliefs of Judaism. In the course of a Saturday class, reserved for questions, he boldly asked the rabbi, "Who made God?"--and the response was a slap in the face. He also tested the laws of his religion. According to those laws, it was forbidden to touch the candlesticks or have anything to do with fire on the Sabbath. At a large Sabbath dinner, however, Ben did touch the lighted candles, just as they were about to fall. Certain that something awful would happen to him because of his defiant act, he was puzzled when he was not punished. He was not chastised, either, when, on another occasion, he defied the laws of his religion by keeping a coin in his pocket throughout the Sabbath. He was, he noted later in his life, being brought up with values that were unacceptable to him.

1998

Howard Greenfeld

Historic Mural "The Meaning of Social Security"

"I feel that the whole Social Security idea

is one of the real fruits of democracy. There may be some limitations to my

powers of exposition, but at least it is my aim to make the mural a clear and

feeling picture of Social Security, and, I hope, one that may be understood by

average Americans."

- Ben Shahn

Letter to Edward Bruce

Section of Fine Arts and Painting

July 14, 1941

|

|

Ben Shahn built his mural "The Meaning of Social Security" around the words of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, giving pictorial form to the President's June 8, 1934 address on the Social Security legislation:

"This security for the individual and for the family concerns itself primarily with three factors. People want decent homes to live in; they want to locate them where they can engage in productive work; and they want some safeguard against misfortunes which cannot be wholly eliminated from this man-made world of ours."

The Social Security Act was passed on August 14, 1935 as part of the New Deal program of sweeping social reforms that responded to the economic crisis of the Great Depression. Shahn's Social Security mural vividly captures the ambitions of the New Deal programs and also serves as an example of government efforts to extend patronage to the arts in the 1930s.

The growth of the arts was encouraged and administered by the Works Progress Administration/Federal Art Project, the U.S. Department of the Treasury, and the Federal Works Agency. As a consequence, original works of art grace many federal buildings in Washington, D.C., such as the Wilbur J. Cohen Health and Human Services Building, originally designed in 1940 to house the Social Security Administration. Murals and sculpture were envisioned by the architects to embellish the thrifty design, enhance the workplace, and contribute to a growing national collection of fine arts.

The Artist: Ben Shahn

|

|

Ben Shahn was born in Kovno, Lithuania in 1898,

migrated to the U.S. in 1906, and died in 1969. A son of craftsmen, the artist

grew up in Brooklyn, N.Y., exposed to both observant Judaism and working-class

socialism. Shahn studied at the Art Student's League, New York University, City

College of New York, and later at the National Academy of Design. He also took

art classes in Paris in the 1920s and traveled throughout Europe and North

Africa. As a struggling, politically active painter during the Great

Depression, Shahn's first critical recognition came from his controversial

Sacco and Vanzetti series (1931-32). This work secured his reputation as a

"social realist" devoted to fighting injustice and promoting the

human rights of underprivileged peoples. Shahn was prolific in a variety of

media: paintings, prints, photographs, posters, drawings, murals, stained

glass, and mosaics, gravitating towards work that could reach a wide audience.

Today, his work can be found in cultural institutions worldwide.

Restoration and Conservation of the

Mural

|

|

In 1993 under the close direction of the U.S.

General Services Administration, Public Buildings Service, the mural was

restored by art conservators, and public access to this significant cultural

asset was greatly improved. On October 17, 1995, "The Meaning of Social

Security" and the Hearing Room Lobby in the Cohen Building were

rededicated to the memory of Ben Shahn and all artists whose works grace

federal buildings by the President's Committee on the Arts and the Humanities,

the Voice of America, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and the

U.S. General Services Administration.

Excerpted from brochure written by Guest

Curator Laura Katzman, Associate Professor of Art, chair of the Art Department,

and director of Museum Studies at Randolph-Macon Woman's College in Lynchburg,

Virginia. Full text available upon request from the Office of Public Affairs,

330 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20237; tel. (202) 203-4959,

e-mail publicaffairs@ibb.gov.

2004

Bernarda

Bryson Shahn, renowned artist, 101

ROOSEVELT - Bernarda Bryson Shahn,

a painter and illustrator who also supported the career of her renowned artist

husband, Ben Shahn, has died.

She was 101

.

|

Art,

as I saw it one day when I helped hang a National Academy show while I was a

student there, was about cows. In those days, early in the twenties, there

were many cow paintings. More than that, the cows always stood knee-deep in

purple shadows. For the life of me I never learned to see purple where there

was no purple -- and I detested cows. I was frankly distressed at the

prospects for me as an artist. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

- Ben Shahn, quoted by Katherine Kuh (found

at Constable.net) |

|||||||||||||||||

|

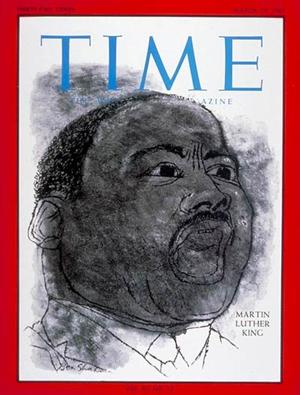

Known for his linear

and abstracted images of humanity, Shahn

became the leading American social realist of the 1930's following in the

tradition of Goya and Daumier. Shahn

launched his artistic career with the famous 1932 paintings of the

Sacco-Vanzetti trial and thus began a lifelong search to express compassion

for the human condition. His subjects ranged from war-torn angst to social

decay and the lonely isolation of the individual. Consistently, throughout a

multifacited career as painter, draftsman, photographer, printmaker and

designer, Shahn

depicted images of contemporary events imbuing them with his deep personal,

political and social views. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Bernarda B. Shahn, 101, illustrator

Bernarda B. Shahn, 101, illustrator

á ROOSEVELT,

N.J. -- Bernarda Bryson Shahn, a painter and illustrator who also supported the

career of her husband, renowned artist Ben Shahn, died Monday at her home

Mrs. Shahn worked in several mediums but gained early recognition for her lithographs.

She wrote and illustrated children's books, including ''The Zoo of Zeus" and ''Gilgamesh." Her portraits of celebrities appeared regularly in several magazines.

Mrs. Shahn continued painting and hosted gallery exhibits well into her 90s. For years she summered in Maine, where she was a central figure in the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture.

Born in Athens, Ohio, Mrs. Shahn studied painting, printmaking, and philosophy at Ohio State University.

In 1932, she met her future husband during a trip to New York. A cross-country trip followed, filled with her work on illustrations and lithographs portraying the disappearing American frontier.

Her husband, a foremost artist of the 1930s, made his reputation painting

realistic New York scenes from the Great Depression. He died in 1969.![]()